Two years ago, to mark Children’s Grief Awareness Week, I wrote a blog because the phrase “children are resilient” had been playing heavily on my mind. I felt it was clouding our view of how children who have been bereaved are treated. One of the points I raised that seemed to resonate the most with people was this: Needing help doesn’t mean she’s not resilient, that she’s mad, that she can’t cope or that she’s weird. It just means she’s human and vulnerable.

A lot has happened since I wrote that blog, but as I sit here today, on the first day of Children’s Grief Awareness Week 2024, there’s a new thought that is playing heavily on my mind. The fact that my daughter won’t ever really remember a life without grief in it. She won’t ever really remember her mum when she wasn’t grieving. Imagine that. Growing up with grief being part of your everyday life. I hesitate to use the word normal, because that is different for all of us, but ultimately grief, trauma and sadness are part of my daughter’s normal and have been since she was 10 years old. It breaks my heart beyond all belief that her innocence and childhood were snatched from her so cruelly.

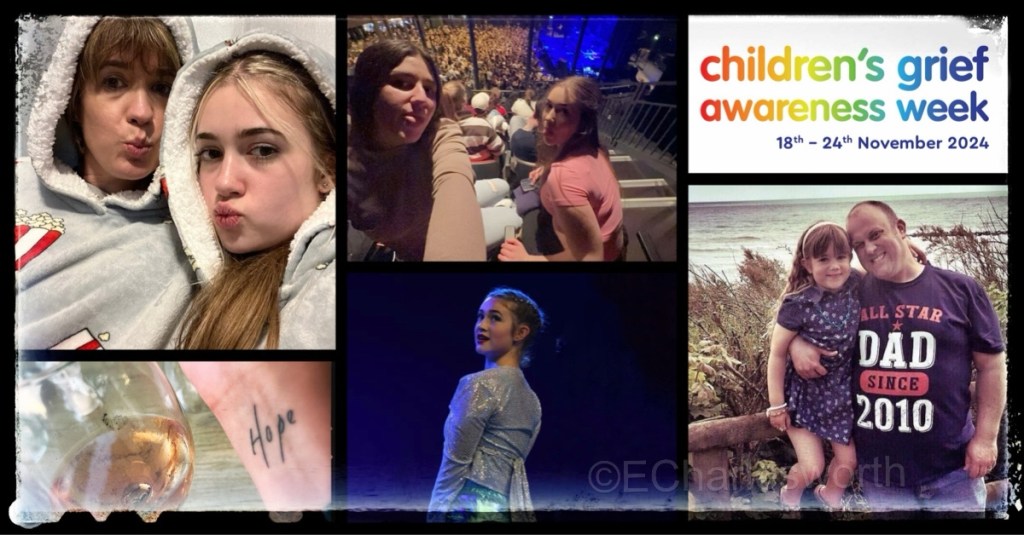

Yet when I started thinking about this a bit more, I started thinking about the theme of this awareness week. #BuildingHope. Hope is probably the most pertinent word in my family. It’s the word I have tattooed on my wrist in my late husband’s handwriting. It’s part of my daughter’s name. And the fact that this grief awareness week begins on 18th November is also something that feels pertinent for me. 18th November 1993 is the date that I first really became aware of death and grief. These two things put together are why I knew I needed to write.

I’ve never really spoken about the fact that I too went through grief as a child. Mainly because in 1993, mental health or speaking about your emotions and feelings weren’t really considered. And certainly not for a child. But more than that. As the years have gone by, I have never really felt it was my story to tell. Yes, my family and friends at the time knew about it. It crops up in conversation with people to this day at times. But I haven’t publicly talked about it. I’ve had numerous different bouts of counselling over the years, but it’s never been a topic of discussion, there’s always been what I’ve felt are more pressing things to talk about. Yet recently I’ve stopped to think about how that day itself, the immediate aftermath and the bereavement I went through, haunts me and continues to affect me to this day. I suspect it always will. It’s a part of who I am. Because it is a part of my story. Whether I talk about it publicly or not.

It almost feels a bizarre coincidence in a way that both mine and my daughter’s first real memory and experience of death happened in what were fundamentally national tragedies. That we’ve both had to deal with death against a backdrop of news headlines and TV images. Such completely and utterly different circumstances, but the similarities are there, nonetheless. I was 12 years old. She was 10 years old. Having to adjust to a new reality without someone they loved in it. Becoming acutely aware from a young age that death can happen to anyone. It’s not just old people who die. Being aware of your own mortality before you’re even a teenager. It’s a lot to have to come to terms with.

I think this is what has led me to the realisation about my daughter having grief in her life forever. And I also think this is part of why I have so vehemently pushed her to talk about her grief. To have counselling. To try to help her process and make sense of the trauma she went through. The secondary losses she has faced. The future she faces growing up without her father. I want to do all I can to help her manage this unfathomable loss. To have it be a part of her story but not her whole story. To help her grow around it.

Whenever I talk about her and what she’s faced in my blogs, I always, always check she is comfortable with what I’m going to write. Because ultimately her experience is her story. There are some things which are just too personal to both of us to ever share. I won’t talk about them. I respect her views. Yet when I spoke about this blog, I could see the progress she’s made since that blog two years ago. The little bits of her life she is more comfortable for me to talk about now.

Shortly after I wrote my blog in 2022, my daughter and I joined Winston’s Wish Ambassador Molly for an Instagram Live together with Grace Lee, Director of Marketing and Communications for Winston’s Wish. The concept was for young people to talk directly and openly about their bereavements and grief. It was a classic case of Instagram vs. reality, in the 10 minutes before we went live, my daughter and I had some minor disagreements, she was stroppy with me, I was conscious of time so was blunt back and then the second we went live we switched on the consummate professional act! But as I sat there listening to Molly and then my own daughter, I was struck by just how astute they both were and how much they understood the impact that their bereavements had had on them. My daughter said things about grief that I’d never heard her say before. There were some real lump in the throat moments for me. I’d have never anticipated quite what was going to come our way just a few months later.

Because it was in February 2023 that I took my daughter to our doctor to get her referred for counselling. Her grief had manifested itself into anxiety. And it was becoming more and more difficult to manage. I’d had an inkling that this might happen the day of her great-grandmother’s funeral in January 2022, it was at the same crematorium as her dad’s funeral, she had to face all his family and by the time we got to the evening, she was shaking on the bathroom floor and vomiting. She couldn’t go back to school the next day. The anxiety and the stress that day caused for her was simply too much for her to deal with. It was another loss for her to have to process.

But by 2023, her anxiety had got to the point where she couldn’t leave the house in the morning for school without eight different alarms. Each of which to tell her it was time to do something else, be that go in the bathroom, get dressed or have breakfast. It felt unsustainable. Any change to that routine, a few minutes lost here and there was enough to cause a meltdown. There were days she didn’t even make it into school. She simply couldn’t process change. Everything had to be regimented. I watched as she withdrew into herself more. We argued more because I couldn’t really understand what she was going through. Because I didn’t understand just how crippling her anxiety had become. Just how hard her life was. Until she started her counselling, all I could do was love her and watch her suffer as she tried to make sense in her mind of why she was like this. As she tried to answer the question she posed herself “why am I like this?” It was, quite simply, heartbreaking to watch.

She was nervous about the counselling. She didn’t really know what she’d say. But as I sat on the stairs and listened to her first session, I could hear her talking. I was astonished quite how much the counsellor got her to say. After that I didn’t listen to her sessions, they were personal to her and I knew if there was a major concern, the counsellor would contact me. But for someone who was such a sceptic, these sessions helped her. Even she would admit this. Just last week, she commented on how she only has one alarm now and it goes off 35 minutes later than it did last year. This might sound small to someone who has never experienced anxiety, but to her it’s massive.

And while a lot of her anxiety has dissipated, it is still there. I don’t doubt it always will be to an extent. It’s part of her grief. We have found ways to help her manage it, but if things come at her left field, they do still cause her to feel anxious or to panic. She will openly admit she has trust issues. She struggles to let people in. She has abandonment issues. I don’t doubt that as she gets older, she will need therapy again. Because at different points in her life, she is going to need help to process her emotions. It’s a fact of her life.

And she’s also had to live with my grief being a fact of her life for the last four years. The fact I find myself crying anywhere, a supermarket, the theatre, in the car, the cinema… the list is endless. We recently went to see Paddington in Peru (I cried!) and on the drive home, we saw an ambulance with its blue lights on. No siren, just lights on. My daughter started making the sound of a siren, I laughed and said, “why are you being an ambulance?” To which she simply said “I know you don’t like seeing the blue lights without the sirens. It’s hard for you so I thought I’d add them.” Deep breath moment for me. The realisation that things like that are on her mind. How acutely aware she is of how I feel and my triggers. Three years ago, she was interviewed as part of a study on childhood bereavement, they asked her how her mum was coping. “She keeps herself busy and doesn’t sit still, because if she stops, she’ll have to think about what’s happened to us and she doesn’t want to do that.” Another deep breath moment. Because there are times her emotional intelligence is off the scale. But this also breaks my heart. She shouldn’t have had to become this astute. She shouldn’t have had to live with grief becoming a part of her world at such a young age that she’s been able to gain this understanding.

Her understanding, vulnerability and honesty are just some of her qualities that I am most proud of. I do believe she’s growing up with an empathy that she wouldn’t have if she hadn’t experienced the loss of her father and watched her mother grieving. She knows this herself. Towards the end of last year, she and I had a conversation in what is known as the “Jac McDonald’s” (mainly because this is where we ate before going to see Jac Yarrow on more than one occasion.) And while I’d rather not be having a deep and meaningful over a Big Mac, sometimes you just have to go with the flow of the conversation. She told me that she wouldn’t necessarily change what has happened to her. I was quizzical over this but the way she responded again just made me so proud. Her rationale was that she likes the person she is now, and she doesn’t know if she would be this person if she hadn’t gone through everything she has. Another deep breath moment for me. There is no real response to that. Without question, she will never cease to amaze me with how she has approached everything and the way she now reflects on her life.

Recently she and a friend went to their first gig without a parent. No way would she have been able to do this last year. And while I was a tad neurotic, when I got the text message from her to tell me they’d found their seats, had bought some merchandise and what time they’d worked out they’d need to go to the toilet before the main act, I breathed a sigh of relief. She’s got this was my overarching feeling. And as her friend’s mum and I waited in the venue for the gig to finish, I listened to the lyrics of one of the songs. The words that Henry Moodie sang felt like the perfect way to sum up my daughter’s response to grief and anxiety:

- I’ve learned to live with my anxieties

- ‘Cause I’ve got some bad emotions

- It’s just a part of life, it doesn’t mean I’m broken

- At the worst of times, I tell myself to breathe

- Count to three, wait and see that I’ll be okay

- ‘Cause I’ve got some bad emotions

- Took a minute, but I’m finding ways of coping.

Anyone who is parenting a child who is bereaved wants to make it better for them. Anyone who has experienced childhood bereavement wants to feel better. Wonders when the grief and the pain might go away. Yet, as I’ve come to realise it doesn’t ever go away. But by talking about it and hopefully breaking some taboos, we can become more understanding of the impact, find techniques for coping and learn ways to support.

#BuildingHope is this year’s theme, and I cannot think of anything that is more fitting. It sounds clichéd. It sounds trite. But speaking as a mother who has watched her child ride the grief rollercoaster these last four years, I do truly believe that building and offering hope to those also experiencing this is one of the most powerful things we can do.

Quite simply. Hope is everything.